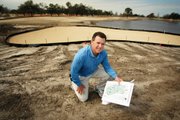

Kelly Gibson on the job

Things haven’t been easy in the Big Easy in the years since Hurricane Katrina pounded the Louisiana coast on Aug. 29, 2005, breaching its levees and destroying everything in its path.

The saints were just beginning to march back in as the city rebuilt itself in the wake of the disaster. Then came the Big Spill last April. According to National Geographic, the Deepwater Horizon blowout resulted in the disgorgement of “nearly five million barrels, making it the world’s largest accidental marine old spill.” We’ve all seen the pictures of oil-covered pelicans snagged in the oil’s gooey brown sludge, but there is at least one bright spot in New Orleans: the revival of the Joe Bartholomew Golf Course.

The storied municipal layout is located within Pontchartrain Park, a suburban-style neighborhood that was one of the first areas in New Orleans to provide home ownership to middle- and upper-income African-Americans. The golf course takes its name from Joseph M. Bartholomew, Sr., who was born in New Orleans in 1881 and later became one of the city’s most successful African-Americans. He learned to play golf at the turn of the last century as a caddie at Audubon Golf Course. He once shot a 62 at Audubon and competed against the likes of Walter Hagen and Gene Sarazen. Demonstrating a talent for course maintenance, he was later made keeper of the greens at Audubon.

After being sent to New York by a group of wealthy private club members to study golf course architecture under the tutelage of Seth Raynor in the 1920s, Bartholomew returned to build several courses in and around New Orleans, including Lake Pontchartrain, a nine-hole course expanded to 18 holes in 1957. The layout is acknowledged as the first course designed by an African-American architect in the U.S. During the segregation era in New Orleans, this course was the only one in the city available to African-Americans. In 1979, the layout was renovated and renamed the Joe Bartholomew Golf Course in honor of its designer, builder and first pro.

Five years ago, Wisconsin-based golf course architect Garrett Gill joined Kelly Gibson, a PGA Tour member and New Orleans native, to complete a multi-million dollar renovation of the course. They were two weeks away from reopening the course when Hurricane Katrina slammed into the Louisiana coast, flooding the course with sea water.

Peter Carew, long-time superintendent for the city’s two municipal facilities, was one of the few golf employees to ride out the storm. He was on hand to assess the damage to the Bartholomew course after Hurricane Katrina blew through.

“The middle of the golf course was under water for over eight weeks,” Carew said, adding that he measured the salt line at 22 feet on trees. “The golf clubhouse sits on a knoll, and it was eight feet under water.” He said redfish, sharks and other native aquatic species were observed in the vicinity of the clubhouse. The facility’s irrigation system and maintenance equipment were destroyed by the storm, as was the turfgrass. Eighty percent of the layout’s oak and cypress trees were killed.

Rather than head for the hills, the design team, maintenance crew and Minnesota-based builder Duininck Golf reconvened after the city of New Orleans earmarked $9.9 million for a complete makeover of the layout. (Funds for the project were obtained through FEMA and a community development block grant).

The rebuilt Joe Bartholomew Golf Course will reopen in 2011

Gill noted that the Joe Bartholomew Golf Course was originally developed as the core of a ‘New Age’ residential community. While noting that Bartholomew only built a handful of courses, Carew said his work, influenced by Raynor, is a byproduct of the Golden Age of golf design and therefore classic.

“We are sensitive to the look and strength of the golf course,” Gill said. “There’s good structure to the course, from its orientation and general configuration of the holes to the distribution of par. Bartholomew laid a great foundation for this golf course. The way these holes were put together is almost perfect. The city of New Orleans is looking to preserve that.” The turf–one type of Bermuda grass on the fairways, another on the greens—is expected to be grown in by November, 2010. The golf course, a critical part of the rebirth of Pontchartrain Park, is expected to reopen sometime next year.

Gill explained that he and Gibson are not looking to technically “restore” the golf course. “The tees and greens have been reshaped, so it’s not pure,” he stated. “The original layout was a low-budget facility, but the basic essence of the routing is good. The new design preserves the original layout while reshaping the property.” The city, he added, is referring to the extensive remedial work as “repairs.”

Gill catalogued the list of tasks that were completed at the city’s top muni. In addition to putting holes back to where Bartholomew had intended them to go, the design team built new tees, dredged existing lagoons and added nine new ponds. “One of the biggest projects was to raise fairways to get some surface slope or topographical relief” on the nearly dead-flat site, Gill said. The layout, surrounded by canals, is a stone’s throw from Lake Pontchartrain. In addition to laying new cart paths, Gill said a new pump station and irrigation system were installed. Also, power lines no longer crisscross the layout.

The dredging had some unintended consequences. “I’ve found golf balls from the ‘50s, ‘60s, ‘70s, ‘80s and ‘90s,” exclaimed Gibson, a fifth-generation New Orleans native. “I found the history of golf unfolding in front of my eyes as we were digging out the lakes.

“We had a unique opportunity to take something historic in nature and bring it back to its full glory,” said Gibson, who assisted Pete Dye on the design of the nearby Tournament Players Club of Louisiana. “I’ve leveraging my PGA Tour experience to help bring the best available talent to New Orleans to fix up its damaged golf courses.” He believes the Joe Bartholomew Golf Course “will be the best golf course in New Orleans” when it reopens, adding, “this might be the most significant thing I’ve done professionally in my career.” With a double-ended driving range that holds a First Tee practice area at one end, Gibson hopes a “whole new generation of golfers” will come of age at the complex.

”It’s important that this course be playable for the 18-handicapper,” Gibson continued, noting that the course has four tee boxes per hole and ranges from 6,823 yards from the tips to 5,314 yards from the forward tees. “I want the course to be enjoyable by golfers at all skill levels. Aesthetically, it will be pleasing to the eye, easy to maintain and will be offered at an affordable dollar figure.

“Hurricane Katrina was a defining moment for New Orleans,” he explained. “Let’s face it, we were hit by the greatest natural disaster in the nation’s history. Out of the devastation, we have seized a very special opportunity at this golf course. When it’s completed, the Joe Bartholomew Golf Course will be a ‘hidden gem’ for both residents and visitors seeking affordable golf. This course is going to be beautiful and a lot of fun to play.” As before, breezes off Lake Pontchartrain will create the challenge, as will the well-placed water hazards and large, subtly contoured greens.

Gill cited the revival of the Joe Bartholemew Golf Course as “a very interesting project from a historical perspective. It’s also an important way to improve morale among the city’s residents. The idea is to bring back this key recreational outlet and make people feel proud again about their community. When the course reopens next year, it will essentially be a new course.” One with a storied and stormy past, he might have added.

After the round, players can check out “Living With Hurricanes: Katrina and Beyond,” a $7.5 million, 6,700-square-foot permanent multimedia installation that opened in October, 2010 in the Louisiana State Museum’s historic Presbytere building in the French Quarter. According to museum director Sam Rykels, “‘Living With Hurricanes’ documents the human struggle in the face of a natural disaster, incorporating everything from survivors’ personal mementos to their thoughts and feelings.” Among the 2,000 artifacts on the display is the ruined Steinway baby grand piano that belonged to “Fats” Domino; the ruby-encrusted clarinet of jazz legend Pete Fountain; and a small hatchet bought by a woman the day before the storm and later used to hack through the attic roof so she and her daughter could escape the rising floodwaters.

Golf Course: (504) 288-0928

Museum Info: www.katrinaandbeyond.com