Jack Nicklaus at the 1986 Masters

Like many golfers who revere Nicklaus as the greatest champion of all, and by that I mean more than the mere accumulation of titles and trophies, I still remember sitting in my drafty New York City apartment 25 years ago with a few friends while we watched Jack peel back the years on Augusta’s back nine. I remember the birdies and the roars that rattled the pines and the sheer inevitability of his victory. I remember Jack stepping away a few times to clear his eyes, and I remember Jackie, much taller than his dad, stoically shouldering the bag.

When I see the replays, the checked pants and the yellow shirt and the furrowed brow and the mop of blonde hair, I recall fondly that most magical of Masters and the way Jack went about acquiring his sixth green jacket. I can see in my mind’s eye his improbable back-nine 30, which snatched the Southern-fried tooniment from Kite, Norman, Ballesteros and a host of other contenders. But mostly when I recall the 1986 Masters, I think back to the day that I and a few lucky others spent a day with Jack in the Cayman Islands.

That was in February, 1985. I had been invited to join a small press contingent sponsored by the Brittania Golf Club on Grand Cayman, the offshore banking and scuba diving mecca situated due south of Cuba.

While he hadn’t won a major in a while, Jack at that time was still regarded as the game’s greatest player. At age 45, he was beginning to leverage his reputation to secure new design commissions. On a warm, breezy day, he arrived in George Town aboard his private jet to formally open a prototype course he had designed to accommodate a revolutionary new ball.

Picture this: Jack steps to the first tee of a heavily mounded, links-style course of his own design. He sets up to the ball in his usual deliberate fashion, and with a mighty swing wallops his tee shot 135 yards down the middle. What? You say your Aunt Tillie could fly it past Jack? Perhaps so, but not with the ball Jack was playing that day.

It isn’t often that someone perceived as a traditionalist reveals a visionary side of himself. As we soon learn, Nicklaus, then-owner of the Macgregor Golf Company, is playing a ball that floats on water, can’t break a window and is stamped with a peg-legged turtle dressed in a pirate’s outfit, the official logo of the Cayman Islands.

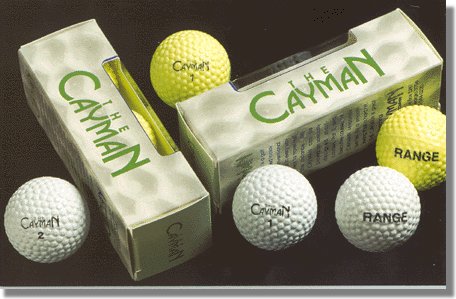

Modeled after the “bramble” ball popular in the early 1900’s, this “short” ball is less than half the weight of a regulation ball and has protrusions (or convex dimples) on its surface. These pimples create aerodynamic drag that slow the ball down quickly. Which is why Jack’s rifled 3-iron shots into the wind barely travel 100 yards.

Inverted dimple Cayman balls

It turns out Nicklaus had toyed for several years with the idea of manufacturing a “short” golf ball so that he and his wife Barbara could play a fair match. When a Canadian developer approached Jack with an offer to build a golf course on a 52-acre rectangle of former mangrove swamp across the street from Grand Cayman’s Seven Mile Reach, Nicklaus figured this was the perfect place to debut his new Macgregor 50 (for 50 percent) ball, which the company had spent $100,000 to develop.

“Our first reaction was, ‘It won’t work,’” Brittania developer Hal Walker tells us before Jack arrives. “We wanted the most spectacular nine-hole course ever built. Jack said he’d build us the nine-hole course so long as he could superimpose an 18-hole course for the short ball.” To calm the developer’s fears, Nicklaus and Bob Cupp, his lead designer at the time, shoehorned an 18-hole, par-57 executive course into the layout, creating an ingenious tri-course. (At that time, a rotation system was used to designate play by either a regulation or Cayman ball).

The course itself is typical of what Nicklaus was building in the mid-1980s. Think of a scaled-down version of Loxahatchee or Grand Cypress in Florida, both known for their prominent mounding. In the case of Brittania, landfill removed to create three lakes was later bulldozed into volcano-shaped mounds to delineate hole corridors on the dead-flat site.

Jack warms to the subject of his novel creation as he strolls down the first fairway. “Certainly it’s cheaper to change the ball for recreational purposes than it is to buy more land,” he says. The obvious future for Cayman golf, he explains, will be in populous areas where real estate for recreational development is limited. Also in water-scarce regions where the cost of maintaining turf grass is prohibitively high.

“I like the fact that Cayman ball courses would be cheaper to build and maintain,” Jack enthuses. “Artificial greens could be installed. Gang mowers would uniformly cut tees and fairways. People can walk around with a skeleton set of clubs and play in half the time.” (Nicklaus himself has three irons–3, 6, 9–and a driver and a putter in the bag).

“A group might be able to play nine holes on a one-hour lunch break,” Jack says, his high-pitched voice earnest as can be. “It might be a good way for kids in urban areas and others who have had no previous exposure to golf to get into the game.”

While it delivers about 50 percent of normal distance with the driver, the Cayman ball plays more like a conventional ball the closer a player gets to the green. A 9-iron travels about 75 percent of the distance of a regular ball. Chipping and sand play is about the same for both balls, as is putting inside 10 feet. Longer putts need to be hit firmer.

Walker admits that despite his reservations about the Cayman ball, he became an immediate devotee of the featherweight sphere with the reverse dimples. “The nicest thing about the Cayman ball is that it promotes a nice, rhythmic swing,” he says. “If you try to crush this ball, it doesn’t go anywhere.” Slightly off-center hits produce sidespin, which the bramble ball exaggerates in the wind. The club must be applied squarely to the back of the Cayman ball for optimum results.

Because of its lighter weight, the Cayman ball sits higher in the grass and is easier to get airborne. It delivers a satisfying click when struck and jumps off the clubface like a conventional golf ball, yet it’s no more intimidating to hit than a ping pong ball. Jack points out that it tends to equalize player ability and makes for a more social game simply because the ball can’t be hit far enough off line for less accomplished players to become separated from their group. Cayman golf, it seems, has a sporty quality that tends to remove the anxieties and frustrations associated with regular golf.

Brittania was built to resemble a Scottish links

We arrive at Jack’s Lilliputian drive. After surveying the approach with his usual seriousness and sense of purpose, Jack drills the ball into the wind, the ball ballooning quickly but carrying the creek fronting the green and hopping towards the pin.

“I’m not trying to revolutionize or replace conventional golf,” Jack says before hunching over the ball in his inimitable putting style. “I’m just trying to market to people we haven’t reached before who can play a variation of the game faster and less expensively.”

When the round is concluded and Jack has graciously shaken hands all around, a few of us ask him if the ball could be used as a teaching aid.

“I found myself swinging more smoothly and hitting the ball more solidly with the Cayman ball,” Nicklaus confides to the four media types on hand after his carefree two-hour round. “To be honest, this ball has helped me slow down and improve my tempo. I really learned a little something today,” he says with a wink before boarding his jet and waving goodbye.

Later that same week, Nicklaus finished a strong third in what was then the Doral-Eastern Open in Miami.

Fourteen months later, he would electrify the golf world with a performance as thrilling as any in the game’s history. And with a swing that bore a very strong resemblance to the once I saw him using to advance a reduced-flight ball imprinted with the logo of a peg-legged turtle dressed in a pirate’s outfit.

(Editor’s note: the Cayman ball has fallen out of favor at Brittania and is no longer used).