The economy seems to be improving. Time to break out the bubbly, propose a toast, wish for better days ahead.

As you gently pry the cork from the bottle, did you ever wonder how fine French champagne, a magical elixir if ever there was one, acquires its distinctive zest? Put another log on the fire. There’s a story that goes with it.

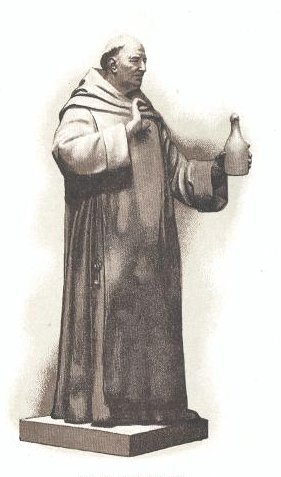

In 1670, a Benedictine monk by the name of Pierre Perignon was appointed cellar-master to the Abbey of Hautvillers near Epernay in the northeast of France. The celebratory destiny of all festive occasions was forever altered by the Dom’s appointments.

Perignon, an inquisitive man, noted the peculiar ability of the local wines to ferment a second time in the spring and began to produce a pale, straw-colored wine with delicate, pinpoint bubbles that rose in tiny strands to the surface and spent themselves in an effervescent froth, or mousse, that tickled the nose. Epicureans said it refreshed the palate. Socialites welcomed it as a messenger of good cheer. Poets claimed it drew the stars closer and intensified their light.

Small wonder that this most irradiating of all wines, named champagne for the region in which it was produced, became instantly popular throughout Europe, especially among society’s leading ladies.

Said Madame Pompadour, a mistress of Louis XV: “Champagne is the only wine a woman can drink and still remain beautiful.” Affirmed Madame de Parabere: “It brings a sparkle to the eyes without a flush to the cheeks.”

In the U.S., champagne made its place in the late 1800s, when wine merchants from French firms set out to convince Americans, specifically New Yorkers, that it was impossible to have a good time without a bottle of the bubbly on hand. These men were seasoned entertainers who traveled the city’s avenues in fancy horse-drawn coaches and were known to enter fine restaurants and order free champagne for everyone in the house. It was a way of establishing brand loyalty that sadly has been lost along the way.

The first lesson learned on a visit to Champagne—I had the pleasure of touring Reims and its environs several years ago—is that while all champagne is sparkling wine, not all sparkling wine is champagne. Authentic champagne is produced in a relatively small region totaling fewer than 85,000 acres located 90 miles northeast of Paris.

The Romans called this part of Gaul Campania, Latin for “open country,” and indeed the region consists mainly of broad rolling plains broken occasionally by long wooded hills that rise above the River Marne. It is not spectacular country. On the plains are orderly rows of frail-looking vines that are trained high, the tendrils stretched along rows of wire like a women’s tresses pulled back on her head.

Few people head north from Paris during their visits to France, preferring the valleys and sea to the south. But a day or two spent in the Champagne district is sure to enhance one’s appreciation for this elite wine and for the people of the region who use their skill and imagination to transform balky raw materials into a liquid work of art.

What makes champagne special? First and foremost, the region’s subsoil.

The north of France is the vast basin of an ancient inland sea that nurtured the development of shellfish and sea urchins. These creatures left behind a thick layer of limey chalk. The roots of the grapevines sink deep into these enriched deposits, and as any Frenchman will tell you, it is the soil that gives wine its style and character.

Second is the climate. Champagne is France’s northernmost wine-growing district. The average annual temperature is only 50 degrees F, the minimum at which grapes will mature and ripen. Yet natural forces conspire to help the grapes. The chalk soil absorbs the heat of the sun and radiates it to the vines at night. Nearby forests regulate moisture variations.

The slight elevation above sea level safeguards the thin-skinned grapes from spring frosts. If the weather is uncooperative, the humble folk of Champagne simply lavish extra T.L.C. on the vines.

“We consider ourselves peasants,” a champagne executive who participates in the harvest told me. “Champagne is produced by the people who look after the grapes, not the marketing staff. The people of the region are very much in touch with the soil and the vines.”

Three types of grapes are used to make most champagne, two of them (surprise) red. Pinot Noir, the same grape used to produce the red wines of Burgundy, provides fullness and strength. Chardonnay, the noblest of the white grapes, is the lyrical note of all champagnes. Pinot Meunier is a more common red grape that lends evenness. The speed of the pressing (by local decree, 444 gallons of juice is pressed from about four tons of grapes) produces white wine from red grapes and avoids oxidation.

With little variation from the principles established by Dom Perignon more than 300 years ago, each champagne house—there are roughly 150 producers in all, though fewer than 20 are widely known—has developed a cuvee, or blend, with its own distinctive style. Some are creamy and toasty, others light and refined. Said a visiting Parisian of the differences in champagne styles, “Just as in lovely types of blondes, redheads and brunettes there are subtle differences of appearance, charm and personality, so too with the different cuvees.”

While Epernay, home of Moet & Chandon, has its admirers, the epicenter of the Champagne district is Reims, a word the French allow to rumble in their throats like the coughing motor of an antique car. Reims flourished under Roman occupation and was a full-grown city known for its grand monuments at a time when Paris was a small community of Celtic fishermen who lived in huts along the Seine.

Destroyed and rebuilt a half-dozen times over the past 2,000 years, the city is dominated by its soaring Gothic cathedral, a veritable Bible in stone that was built in an age when most parishioners were illiterate but could read the parables carved into the porticoes.

Like other great cathedrals in Europe, the Reims church has witnessed much history. Ground was broken for it in 1211, but heavy cost overruns ensured. Expenses mounted so high that the citizens of Reims eventually ran the bishop and his builders out of town. The entire city was excommunicated from the church for its actions. Construction resumed after amends were made. The cathedral opened in time for Joan of Arc to crown Charles VII her king in 1429.

Thousands of limestone saints, hundreds of gargoyles and a handful of smiling angels decorate the cathedral. The beautiful stained glass windows, which brighten and darken subtly as the clouds gather and disperse overhead, are noteworthy. Many were blown out of their frames during World War I. When peace came, the city’s long-suffering residents picked up the shards of glass from the sidewalks and reassembled the windows. Most depict traditional Bible scenes, though several panels donated by local villages portray vineyards, a winepress and the harvest. They do not seem out of place in Champagne’s great house of worship.

Many of the top champagne houses in Reims are built atop a maze of underground chalk cellars where wine that is soon-to-be-champagne is kept. At least one should be visited to see how champagne is made. I chose Pommery, one of the older houses, and was guided through miles of chalk galleries 100 feet below street level by chief winemaster Prince Alain de Polignac, whose great-grandmother was one of the first to develop a brut (bone dry) style of champagne. (Up until the 1840s, champagne was made very sweet).

I was advised to dress warmly for the champagne cellar tour, and for good reason. The chilly chalk caves, their walls encrusted with mold and glistening with dew, are a constant 50 degrees year-round. The temperature is ideal for the graceful maturation of champagne.

In galleries large and small, some with fantastic scenes of drunken revelry carved in the soft walls, thousands of bottles repose in slated A-shaped racks called pupitres. They are turned or “riddled” daily by a remueur to slide the residue of fermentation to the neck of the bottle.

In addition to rows of standard size and magnum bottles, several of Pommery’s racks contain gigantic bottles with exotic biblical names: jeroboams (three liters), methuselahs (six liters) and salamanazars, these last a nine-liter bottle hand-blown in Italy that in size and weight resembles a torpedo charge. Definitely for two-fisted drinkers.

At one point during the tour, Prince Alain presided over an informal tasting. “No special reason is required to drink champagne,” he confided. “All reasons are acceptable.” His comment called to mind the story of a London reporter who asked Madame Lilly Bollinger, legendary director of the eponymous champagne house, when she drank the bubbly: “I drink it when I’m happy and when I’m sad. Sometimes I drink it when I’m alone. When I have company I consider it obligatory. I trifle with it if I’m not hungry and drink it when I am. Otherwise I never touch it—unless I’m thirsty.”

A gracious host, Prince Alain raised his glass to toast our good health, inviting us to admire the color, listen to the music and inhale the perfume of the wine before tasting it. To hear the Prince tell it, champagne is something of a miracle. Secondary fermentation is sparked by a dosage—cane sugar melted in aged champagne—that interacts with the yeast elements in the wine. But exactly why the bubbles form remains a mystery to science.

Ironically, though the Champagne district produces the most elegant wine in the world, it hasn’t the cuisine (with a few notable exceptions) to match it. Ever since the invasion of the Visigoths in the fifth century, the French of the north have been so busy defending themselves in wars large and small that they’ve had little time to evolve a cuisine worthy of their wine. Commented one Reims native, “When you see an army approaching on the horizon, you hardly think about making a sauce.”

The major exception is Chateau Les Crayeres, a classically-styled palace built in 1904 for a Champagne heir that now offers 20 sumptuous guest rooms to discerning travelers. The rooms, awash in heavy brocades and period furniture, look to a lovely wooded park that embraces the ivory-colored chateau. Le Parc, the wood-paneled dining room, is billed as the only place in the world dedicated to the full enjoyment of champagne, and indeed the Menu Tradition de Champagne pairs a different style and vintage of champagne with each course. Serious “foodies” extol Le Parc as one of the finest hotel restaurants in the world.

I like a grand dining experience as much as the next person, but returned twice during my visit to Le Vigneron, a popular corner restaurant in Reims decorated with the tools of the wine trade—oak barrels, woven baskets, a large corkscrew press. The moderately-priced entree of choice here is a salt-of-the-earth dish called Potee Champenoise. It contains white beans, Savoy cabbage, mild sausage, ham hocks, leeks, turnips, carrots, potatoes and celery roots, all of it served with a grainy local mustard on the side. Like others around me, I washed it down with beer.

Accustomed to sniffing and observing before drinking, I noticed that the bulky, aggressive bubbles in the beer wobbled to the surface like the silver globules expelled underwater by a scuba diver. Not only were they are a far cry from the tiny rapid bubbles in champagne, when I put my ear to the glass, I did not hear the angels sing.